[Ferro-Alloys.com] Strategic Minerals at the Forefront of Diplomacy: 2025 in Review

Throughout 2025, the Greater Caspian Region aimed to improve its standing in the world as a source of critical minerals potential. Although China’s and Russia’s grip on the mining industry remains strong in Central Asia, the region itself has sought to diversify its economic partnerships westward, beyond its immediate neighbors. Regional governments look to leverage critical mineral deposits to attract investment from a multitude of partners, namely the United States and the European Union (EU). As they seek to diversify their mineral supply chains away from China, the nations of the Greater Caspian Region can build off progress in 2025 to secure the region’s posture as a potentially competitive alternative.

Key Initiatives in 2025

Kazakhstan and Uzbekistan stood out as frontrunners in minerals diplomacy and diversification. Uzbekistan possesses some of the world’s largest deposits of copper, tungsten, tellurium, and gold. It also ranks fifth in global uranium production.

In March, Uzbekistan announced investments of $2.6 billion to develop 76 mining projects over the next three years, in alignment with C5+1 dialogue and a 2024 U.S.-Uzbekistan memorandum of understanding (MoU). In April, Uzbek officials met with U.S. business executives in Washington, where the two parties agreed to deals on exploration and processing. U.S.-Uzbekistan ties only strengthened throughout the year in the buildup to the C5+1 Heads of State Summit in Washington on November 6. There, Uzbekistan and the United States pledged up to $400 million into the critical minerals industry, strengthening U.S. supply chains. Meanwhile, Uzbekistan signed an enhanced partnership agreement with the EU, which included investments of 10 billion euros into various sectors, namely critical minerals and logistics.

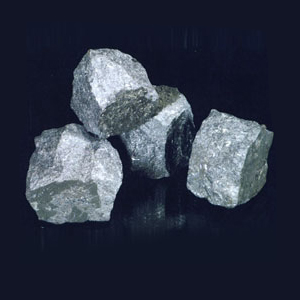

Within its vast territory, Kazakhstan possesses a wealth of unexplored and untapped mineral deposits. Globally, it ranks first in production of chromite and unenriched uranium, seventh in zinc reserves, eighth in copper production, ninth in silver production, and tenth in production of bauxite—a critical ore for aluminum and gallium extraction.

In April, German mining company HMS Bergbau AG agreed to invest $500 million into lithium extraction and processing facilities in the East Kazakhstan Region. In the summer, Kazakhstan established plans with $20 million from Eurasian Resources Group to open a gallium mine in late 2026, equipped with on-site processing to produce up to 15 tons. Tau-Ken Samruk, a Kazakh national mining company, and Cove Capital LLC, a U.S. firm, agreed to commence rare earths exploration in the Kostanay region, which comes after Kazakh geologists claimed the discovery of over 20 million metric tons of rare earth metals in April. Overall, the country attracted over $150 million in exploration investment.

At the C5+1 Washington summit in November, Kazakhstan and the United States signed an MoU on deepening critical minerals cooperation, ramping up minerals exploration, and shoring up supply chains. Moreover, Cove Capital announced an agreement with Kazakh state mining company Tau-Ken Samruk to quarry the world’s largest undeveloped tungsten deposit. Tungsten serves many functions, ranging from energy and electricity conduction to military applications. An on-site processing plant will accompany the mines at the Northern Katpar and Upper Kayrakty deposits in Karaganda. The project will cost $1.1 billion, and the U.S. Export-Import Bank will provide $900 million for capital expenditures.

China and Russia Stand Firm in the Mining Sector

Furthermore, as the largest unenriched uranium producer in the world, Kazakhstan continued its exports to its primary customers with enrichment capabilities—Russia, China, Canada, and France. However, dependence on enrichment capabilities abroad restricts its circle of partners, and so Kazakhstan selected Russia’s Rosatom and China’s CNNC to back its own plans for civilian nuclear power plants.

Throughout the region, China continued to bolster its already-established Belt and Road (BRI) mining projects. Beijing receives raw materials from mines in Tajikistan, from which it processes antimony, a critical mineral with defense applications. Tajikistan is the second-largest producer of antimony in the world, and China-Tajikistan ties only continue to grow, although security concerns at mines remain a concern. A similar story plays out in Kyrgyzstan, where Chinese firms control stakes and licenses in the country’s gold mines. Chinese-owned mines, however, remain controversial because of labor conditions, environmental concerns, and accusations of taking jobs away from locals.

Looking at the South Caucasus, in February, the Armenian government offered a $150 million loan to fund the opening of the Amulsar gold mine—a project under U.S.-Canadian company Lydian Armenia that is challenged by environmental contamination concerns. Gold itself is not considered a critical mineral, but there is significant demand for byproducts found in ore at gold deposits. Armenia’s economy also relies on the extraction of antimony, copper, magnesium, molybdenum, and zinc, although though Russia owns Armenia’s largest mines for these minerals.

Perhaps more notably, the August peace agreement that Armenia and Azerbaijan initialed facilitates the projected establishment of the Trump Route for International Peace and Prosperity, commonly known as the TRIPP Corridor. The corridor aims to increase more direct throughput on the Middle Corridor between China and Europe and could serve as a key lever in the future for unlocking U.S. and EU access to minerals from Central Asia. However, aside from the high logistical costs of transit to the United States along the current corridor, so far the route lacks sufficient capital to achieve East-West commercial viability. Furthermore, geopolitical risk versus mineral reward is a challenge to some investors’ confidence, given instability in neighboring states and proximity to Russia, China, and Iran.

Looking Ahead

Several states in the Greater Caspian Region made important strides on connectivity and minerals diplomacy in 2025, but diversification of the sector still remains limited. Shipping volatility and interstate misalignment in customs and railways create bottlenecks along the Middle Corridor. Because both Russia and China stand as the primary investors in its development, the U.S., the E.U., and other investors would have to provide over $20 billion in the Middle Corridor’s transit infrastructure, and perhaps more into local energy grids to facilitate intensive mining processes that are projected. This strongly indicates the importance of turning towards other interested actors for financing as well, such as the EU, East Asia, and the Gulf States.

The U.S. has demonstrated a clear interest in friendshoring to counter China’s dominance over critical mineral supplies, striking a number of deals with alternate suppliers and refiners. The United States signed a deal to fund Ukraine’s post-war reconstruction in exchange for access to strategic mineral deposits, and it seeks to secure cobalt and copper supply by mediating peace between the Democratic Republic of the Congo and Rwandan-backed militias. In October, the United States signed an $8.5 billion agreement with Australia on critical minerals cooperation, and it continues to strengthen minerals diplomacy with South American states like Argentina.

These deals suggest that the United States will continue to take the threat of Chinese minerals dominance seriously, and the Greater Caspian Region can still compete for a role in this calculus. To turn these hopes into reality, regional actors must continue to enhance connectivity along the Middle Corridor and rapidly fill gaps in their mining industries through directed investment and cooperation within and beyond the region.

- [Editor:tianyawei]

Save

Save Print

Print Daily News

Daily News Research

Research Magazine

Magazine Company Database

Company Database Customized Database

Customized Database Conferences

Conferences Advertisement

Advertisement Trade

Trade

Tell Us What You Think